Written by Owen Myers. In appreciation for the installation of the F-105 Thunderchief into the American Heritage Museum’s Vietnam War exhibit.

It is July 24th, 1965, and United States Air Force Captains Richard Keirn and Roscoe Fobair are flying in their F-4 Phantom escorting a strike package of F-105 Thunderchiefs on their way to strike a weapons facility near Hanoi, North Vietnam. It’s been a quiet day, they were far too high to worry about antiaircraft artillery (AAA) fire. Their gazes crisscrossed the skies in search of Migs.

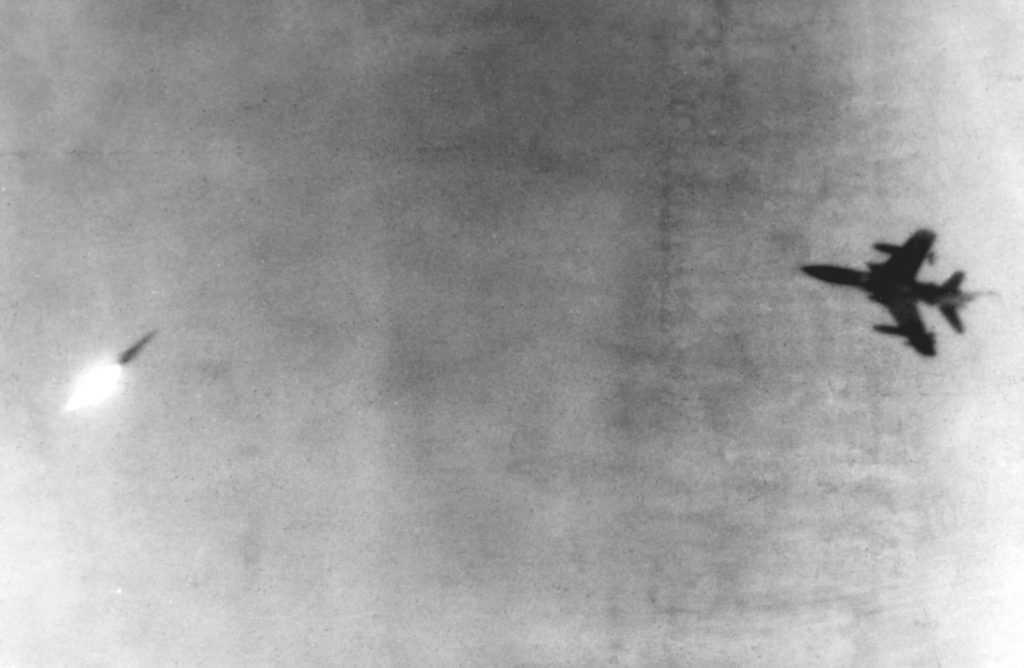

Without warning, a massive explosion rocked their aircraft. One of their wingmen stated that their wing seemed to burst into flames. Immediately, the aircraft began to roll and fall  out of formation. Realizing the aircraft was beyond being saved, Capt Fobair pulled the handles atop his seat and ejected from the stricken airplane. It is unknown if Captain Keirn was able to eject or lost his life before his F-4 crashed. Captain Fobair spent the next 8 years as a POW, not yet knowing that his aircraft was the first of over 100 lost to a yet-unknown factor in the air war blossoming over Vietnam. Captain Fobair and Keirn’s aircraft was shot down by a Surface-to-Air Missile, or SAM.

out of formation. Realizing the aircraft was beyond being saved, Capt Fobair pulled the handles atop his seat and ejected from the stricken airplane. It is unknown if Captain Keirn was able to eject or lost his life before his F-4 crashed. Captain Fobair spent the next 8 years as a POW, not yet knowing that his aircraft was the first of over 100 lost to a yet-unknown factor in the air war blossoming over Vietnam. Captain Fobair and Keirn’s aircraft was shot down by a Surface-to-Air Missile, or SAM.

It’s not that SAMs weren’t known by the United States in 1965. In 1960, a U-2 spy plane flown by Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union by an SA-2, prompting the CIA and USAF and Lockheed to develop reconnaissance aircraft that could fly higher and faster, culminating in the fastest air-breathing jet in the world, the A-12 Cygnus/Oxcart and the SR-71 Blackbird. But in the conflict brewing in Southeast Asia, nobody in the US seemed to be aware the North Vietnamese were also receiving SA-2 missiles and radar sets from the Soviets, a process started in 1964, along with enough training to make them just as lethal as they were nestled deep within the motherland.

The S-75 Dvina (NATO reporting name SA-2 “Guideline”) missile acquired its target and was guided to it by radio control via the SNR-75 radar, known to the United States as “Fan Song.” The Fan Song radar could only track and fire on one target at a time, but had three separate radio control channels to aim three separate missiles simultaneously. The S-75 missile could reach a top speed of mach 3 and had a 430lb (195kg) warhead that could spread fragments in a lethal radius of between 200-800 feet (65-250 meters) depending on the altitude the missile was guided to. Their accuracy was roughly 250 feet (75 meters,) hence they were typically fired in salvoes of three, to ensure a lethal hit. The radar waves (also known as radiation) from the Fan Song could be detected by equipment mounted in EB-66 Destroyer bombers, converted for just such purposes. The issue was twofold; the average fighter/bomber in the USAF wasn’t fitted with any kind of radar detecting gear, and it was too large to fit in an aircraft the size of a fighter. Therefore, the most warning a pilot over North Vietnam got of being fired on by SAMs was a detached, faraway voice saying “blue bells are singing,” meaning a Fan Song was transmitting.

After more jets were lost over North Vietnam to SAMs, it was decided that something must be done to neutralize the threat. Starting with the venerable F-100F two-seat Super Sabre and working closely with companies like Texas Instruments to develop smaller versions of the same gear used in the EB-66, the USAF loaded up the back cockpit with sophisticated equipment, soon known as Radar Homing And Warning, or RHAW, gear. It was the first time The USAF decided to place an Electronic Warfare Officer, or EWO, in the back seat, who could determine the type of radar tracking them and locate it. With the information at hand, the F-100 could guide F-105s laden with bombs onto the site, “killing” it, and allowing the strikes heading into Hanoi to breathe easier on their way in and out of the area.

This was the first time that an Electronic Warfare Officer would find themselves on the “front lines” of combat against SAMs. The average fighter pilot during this time was like any fighter pilot; brash, confident, self-assured; exactly the kind of person one would want facing down the threat of missiles being shot at you, as well as radar-guided AAA. The EWO, who at this point typically sat in the back seats of a B-52 bomber, or in the windowless converted bomb bay of an EB-66 Destroyer, was now confronted with the wide open view from the back seat of a fighter, having to manipulate the RHAW gear while being thrown around doing hard maneuvers, and at any point, you could lose the fight and be shot down.

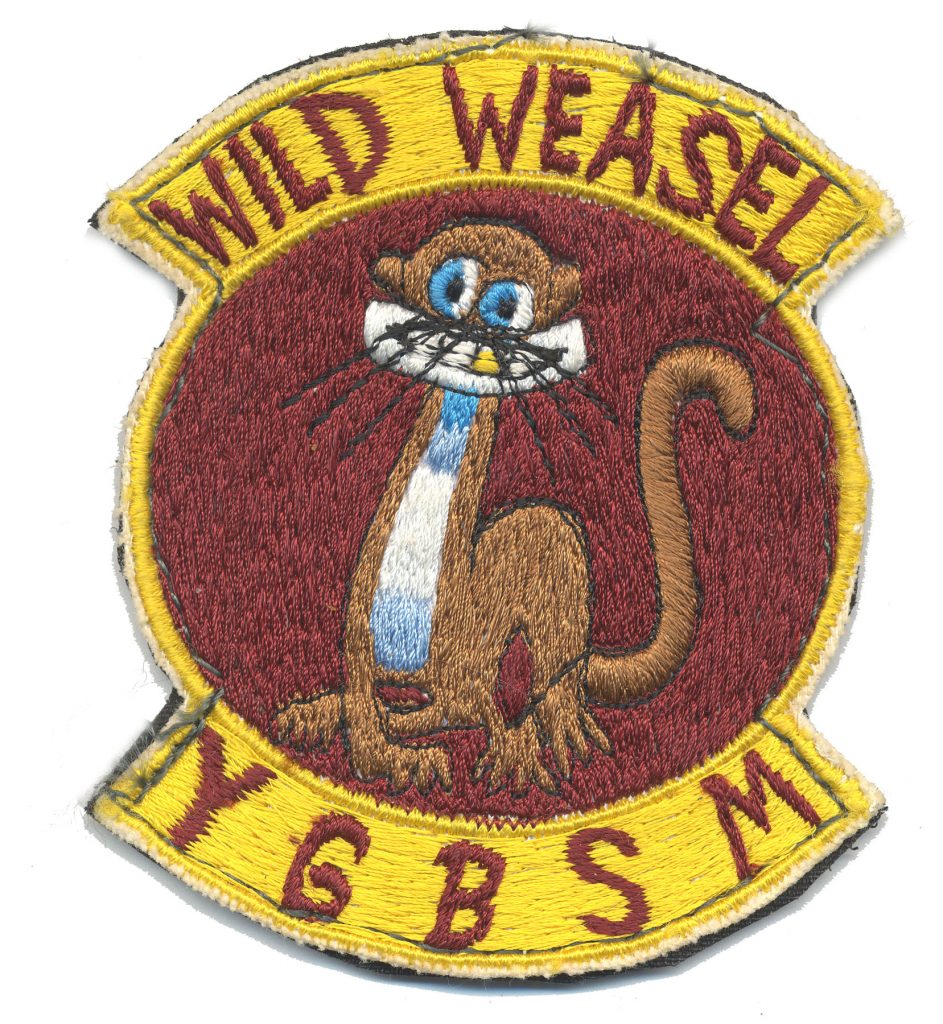

Famously, one such EWO named Capt. Jack Donovan, when he was introduced to the tactics of these new squadrons, said “you want me to fly in the back of a little tiny fighter aircraft with a crazy fighter pilot who thinks he’s invincible, home in on a SAM site in North Vietnam, and shoot it before it shoots me, you gotta be sh*tting me!”

Originally named “Project Ferret” because Ferrets killed their prey by entering their dens, a different name was chosen to separate it from a similar project from World War Two. The new name that was chosen for the project was “Wild Weasel” and the acronym “YGBSM” found its way onto the squadron heraldry as well.

On December 22nd, 1965, the Weasels drew first blood. Captain Donovan and his pilot, Captain Allen Lamb were covering a strike in the northwestern parts of Hanoi when they were “painted” by a SA-2 site. Guiding Capt. Lamb onto the site, Jack Donovan watched as  a heavily camouflaged Fan Song van came into view, before Lamb attacked it with a combination of rockets and gun, when the site went offline. The F-105s in their charge used cluster bombs and rockets to destroy the remaining missiles and infrastructure. A message sent to the joint chiefs of staff simply read:

a heavily camouflaged Fan Song van came into view, before Lamb attacked it with a combination of rockets and gun, when the site went offline. The F-105s in their charge used cluster bombs and rockets to destroy the remaining missiles and infrastructure. A message sent to the joint chiefs of staff simply read:

“Weasel Sighted SAM – Killed Same”

Even as successful attacks on SAM sites started rolling in, issues were beginning to emerge. Mainly with the aircraft the Weasels rode into battle. The F-100F served well up to that point but it was beginning to struggle in the environment of North Vietnam. The first Weasel squadron, the 354th out of Takhli, Thailand, had lost all but one aircraft after 45 days of operations. The human cost was steep too. Of the 16 Weasels, four had been killed, three were wounded but rescued, two had quit, and two were shot down and became POWs.

Clearly, a jet with more speed and survivability was needed.

One choice was the F-4C Phantom. Still a “young” aircraft by this point, the problem became fitting all of the electronics into the airframe, so it was passed over.

The next was the F-105 Thunderchief, and it was a winner. The F-105 was spacious, it was fast, and, most importantly, more survivable than the F-100. As an added bonus, the airframe was the same between the Wild Weasels and the other strike aircraft, meaning maintenance was the same, and nobody had to slow down or burn extra fuel enroute to or from the target area. Two-seat combat capable trainer variants of the aircraft, the F-105F, easily accepted all of the Weasel gear and quickly became a staple of Operation Rolling Thunder. Additionally, the AGM-45 “Shrike” anti-radiation missile was introduced, which gave the Weasels limited standoff capability against the SA-2s and the Fan Song Radars. Jamming equipment was available, but not typically carried, since the Weasels purpose was to be a decoy, and bait the SAM sites into shooting at them.

Tactically, the Weasel mission was known as Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses, or SEAD. Simply forcing the Vietnamese radar operator to shut his radar off in fear that a Shrike was heading his way was enough to protect the strike forces, though destruction of the site (creatively called DEAD) was preferred. Weasel crews would coordinate between firing Shrikes to force the operator to shut his set off, then having other aircraft bomb it to put it out of commission for good. On the ground, Vietnamese radar operators would use one radar to lure the Weasels into attacking it, while another would be firing and homing missiles on them. Soon, some EWOs could tell when a specific operator was seated in the radar van that day, depending on how they reacted to specific attacks. It became a game of chess, where the Weasel didn’t know where all the pieces were placed until they flew near them, and no two days were the same. The days were long; to properly protect the strikes headed towards Hanoi, the Weasels would be the first in the area to suppress the sites, and would keep them busy for the entire time the strike was in the area, being the last to leave. “First In, Last Out” became another Weasel creed.

As Rolling Thunder came to a close, the F-105Fs were progressively upgraded with more gear, most notably the AN/ALQ-105 Electronic Countermeasure system, mounted in blisters along the sides of the Thud’s fuselage. These upgrades and updates to counter the evolving landscape of electronic warfare, often done by technicians from contracted electronics companies on the ground in-country, morphed the aircraft into the F-105G. One of the 61 F models converted was serial number 63-8336, which was ready just in time to take part in Operation Linebacker, protecting the waves of B-52s on their missions. Just like before, when the bombers would come under threat, the Weasels would dive into action, destroying the sites or forcing them to shut their radars off. To many pilots, Linebacker was what Rolling Thunder should have been from the beginning, but by the time Linebacker was in full swing, it was too late to force the North Vietnamese into total submission.

By the end of the conflict in 1973, barely ten percent of all B-52s sent in on Operation Linebacker I and II were shot down by SAMs. Unbeknownst to the Weasel pilots, North Vietnam was beginning to run low on missiles, mainly because of internal strife between the USSR and Communist China. The rift developing between the two powers left North Vietnam more closely aligned with China, which couldn’t supply SA-2s. The North Vietnamese were being more conservative with their missiles, it wasn’t quite like the heady days of Rolling Thunder anymore. The war in Vietnam came to a close not long after with the withdrawal of US forces.

But, success for the Wild Weasels didn’t come without sacrifice. Over the course of the Vietnam War, 34 Weasel aircraft were shot down, 30 pilots were Killed In Action, 19 became POWs, two died in captivity, and 17 were rescued.

For a small squadron in its infancy, every loss was a hammer blow. Every Weasel pilot and EWO were part of an elite group, and esprit de corps ran through the whole squadron, where teamwork and defending your fellow pilots in the harsh skies over North Vietnam stood above everything else.

The Wild Weasels live on today, with an incredible lineage going from Vietnam, through the Gulf War, into the Global War on Terror and the present day. The 480th Fighter Squadron continues to perform the Weasel mission today, based out of Spangdahlem, Germany. The 35th and 37th Fighter Wings fly with the “WW” tail code to show their lineage to the units that flew in Vietnam.

It is with great reverence and pleasure that the American Heritage Museum presents the F-105G 63-8336, named “Patience” by its crew.

As one tours around the aircraft, it’s easy to see how the F-105 got its moniker “Thud” as the first pilots that flew them thought it would be too large and heavy to take off, the “thud” being the sound it made when it crashed at the end of the runway. A vigilant visitor will also spot the ECM/RHAW blisters along the sides of the fuselage, as well as the signatures of the crew that flew Patience’s final mission in Linebacker II on the inside of the landing gear door.

This author would like to pass along appreciation and thanks the Wild Weasel Society for all of the information it has freely available on its website, as well as Dan Hampton, author of “The Hunter Killers” which is an excellent source of information on the Wild Weasels in Vietnam.